Written and presented by Lorna Steele, to the First Unitarian Church of Providence in June 2024. Winner of the 2024 Albert Schweitzer Award.

Article II and The Care of All Beings

Invocation:

“I think it’s a deep consolation to know that spiders dream, that monkeys tease predators, that dolphins have accents, that lions can be scared silly by a lone mongoose, that otters hold hands, and ants bury their dead. That there isn’t their life and our life. Nor your life and my life.

That it’s just one teetering and endless thread and all of us, all of us, are entangled with it as deep as entanglement goes.”

~Kate Forster

Reading:

Emily Dickinson, a Transcendentalist poet, wrote,

“If I can stop one heart from breaking, I shall not live in vain.

If I can ease one life the aching, or cool one pain,

Or help one fainting robin unto his nest again,\I shall not live in vain.”

Sermon:

Article II and The Care of All Beings

Of all the UU principles that I hold dearest, Article II includes in its language about the interdependent web: “We covenant to protect Earth and all beings from exploitation.” All beings. How do we honour that?

UU Reverend Joyner suggested a UU blessing, “May my understanding of the worth and interdependence of all life comfort me and keep all beings from harm.”

To paraphrase Brittany Michelson, “In our interconnectedness, we should acknowledge that all beings have the capacity for love, joy, pain, and fear.”

So there’s a lot of language out there about our connection to animals, but what happened to make that something we had to relearn?

In the very earliest versions of the Christian writings and of the Jewish Talmud, God gave us plants to eat and animals for companions. Over the centuries, more and more exceptions were made until finally society in the western world ended up with a hierarchy of man over animals. Dominion. And not a gentle one. That has been our role. I challenge that, and as UU’s, we must all do so.

In his research, Frans de Waal shows us that many animals are predisposed to take care of one another, come to one another’s aid, and, in some cases, take life-saving action. He has found that chimpanzees care for mates that are wounded by leopards, elephants offer “reassuring rumbles” to youngsters in distress, and dolphins support sick companions near the water’s surface to prevent them from drowning. Do we do the same for them or each other? I would say there’s much gentleness we can show to each other. But to animals? Not enough.

Animals are the North Star of my spirituality. I’d like to believe that they might become one of your compass points. When we talk about the interconnected web or the inherent worth, I don’t merely picture humans, but all beings. And we don’t allow them what they are due. Ryan Phillips said,”Animal rights are not a gift we give to animals. They are a birthright we have taken from them.”

When I was a child in Saigon, I was given a little yellow duckling as a pet. Her feathers were soft fluff, her eyes black and curious. I named her Genevieve, and we had tea parties tucked partially hidden in some bushes I liked, with bits of greenery floating in her cool water. I was a shy child in an increasingly war torn country, and she was my only constant. I loved her, and I think she loved me. As she grew older, her yellow fluff turned to white feathers, and she would waddle quickly toward me when I walked out to the courtyard of our home. One day she didn’t come when I came home from school. I couldn’t find her as I looked frantically all over our property. That night, we were served duck at dinner, and I realized that the duckling that I’d nurtured and loved had become a meal. Just food. My heart broke, the first of a thousand times it would, and it took me many years to trust a human again. It was also, I think, the beginning of a lifelong care for the well-being of animals.

We moved to Thailand, and my brother and I rode elephants. It wasn’t until decades later that I learned that those elephants, to be tamed, went through a process called Pahjaan. It was a breaking of the spirit by beating, the pinning back of their ears with metal, and confinement. This would be inflicted on babies, after their families were killed. I’ve never again been able to see an elephant without remembering that. How cruel we humans can be.

This past spring, a puppy hoarding case was discovered in Pawtucket. 46 dogs were rescued from 6 inches of feces, their coats pounds of matted fur causing pain and temporary blindness, and rear ends so encased with feces and urine that they were scalded from ammonia. Their condition was so bad they had to receive sedation to be shaved. Most were able to be medically rescued. Seven of the dogs died, despite emergency care. The couple who had them was charged with 46 counts of misdemeanors. Misdemeanors, not felonies, despite the lives at risk and actually lost.

What those puppies have in common, regardless of whether they were hoarded or as many others, milled, is a society that views them as property. The duckling, the elephant, the dog. They’re not fellow beings with a need for and a right to food, water, a clean place to live, and kind care. Their fear and confusion don’t matter to the people who do these things to them.

Nor to the people who abandon their dogs alongside a road, to get hit or to starve. Those dogs don’t know what happened, and wait for their owners to return. I have a major soft spot for dogs, as anyone who has spent time with me knows. They have this unwavering loyalty to the people they love, this conviction that their person would never harm them. For those dogs, sometimes their trust is broken forever, but oftentimes, despite their confusion, they hold on to hope.

Jeremy Bentham said, “The question is not whether they can reason, nor can they talk, but can they suffer.” And we know that they can.

And then there are factory farm animals, perhaps the hugest animal rights issue in this country. Naively, I used to think the cruelties only applied to animals for meat. Now I know better. Matthew Scully, the author of Dominion, a landmark book in the animal rights movement, wrote, in his new book, Fear Factories, “the bright, sensitive pig dangling by a rear hoof as it’s processed along, squealing in horror; the veal calf taken from his mother, tethered, and locked away in a tiny stall for all of his brief, wretched existence. It would make us sick to watch, and yet our demand for the resulting products” and here I’ll continue in my own words. The demand makes us turn a blind eye. We don’t want to think about the slaughter of beef. Or the violence against pigs, females confined to metal gestation crates where they give birth on concrete, and males controlled by being struck on the snout with a board or metal bar, called “boar bashing”. And that’s just one set of abuses. Then, pieces of their bodies are wrapped neatly in cellophane, in the meat section of a supermarket. They’re faceless, without personality or connection. Just food. I’ve always wondered how humans can be so viciously cruel.

In the dairy industry is the processing of chickens, crowded together in cages so small they can’t spread their wings, their beaks cut so they don’t fight with each other, lying in their own filth and experiencing urine scald, to produce the eggs that are also neatly offered in supermarkets. I didn’t know that male chicks, being of no use to the egg industry, are ground up alive in a macerator. Chickens that should be like my own, wandering carefree, social, safe, and loved. But they’re not.

We don’t want to think about the cows in the milk factories, artificially inseminated, to become pregnant again and again to produce the milk they give through the machines they’re hooked up to. And when they can no longer do that, are sent to slaughter. The calves they give birth to are removed from the mothers immediately, never to bond or nurse. And yet, even without that formal bonding, mothers will bellow in mourning for their babies. And the babies will cry out in terror and longing. These are all social, gentle animals who should be in a meadow, with the sunshine on their backs.

Ironically, those same animals we abuse, often show kindness to each other as de Waal said. I read a story by an animal rescuer who was trying to get away with a downed sheep for veterinary care, and one of its companions had managed to escape with them and leant her head down to nuzzle her friend, clearly distressed. The downed one cried, bleeting softly for help from both the sheep and the human. The rescuer ended up taking them both.

My favourite poet, Mary Oliver, also a UU, ended one of her poems with the question, “Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?” We have choices. Animals do not.

We lived in Singapore, and then Malaysia. Where American girls might become obsessed with horses, I developed an adoration of orangutans. They were, to my child’s eyes, just big and goofy. I didn’t know that in fragmented rainforests in Borneo and Sumatra, great swathes of trees and habitat were already being bulldozed for the lucrative production of palm oil. But each time a bulldozer cuts through a swath of jungle, it creates a large naked landscape, destroying thousands of acres, and taking the lives of many orangutans and other vulnerable species, left to starve without the trees that sustain them.

And yet, despite all that we have done to them, photographer Anil Prabhakar was able to take a photograph for CNN, several years ago, of an orangutan stretching out his hand to help a man who had fallen into a mud pool. That orangutan showed sympathy and care. When the photographer uploaded the photo, he wrote something like this as a caption: “In a time when the concept of humanity dies, sometimes animals lead us back to the basics of those principles.”

The estimate of the number of animals killed for human consumption alone is almost 93 billion a year. Wrap your head around those numbers. 93 billion lives. And not just killed, but their brief lives deprived of joy, unable to live without loss and terrible pain.

Emily Barwik wrote, “We have an overwhelming sense of loss–not the loss of lives itself, but the complete and utter disregard for these losses.”

They are so insignificant to us that we literally cannot even acknowledge them if we tried. And even when we try, we come up short, forget those whose prolonged suffering would most gladly be met with death, and in the end, reduce them even further into abstraction.”

There are so many, too many, areas and issues of animal abuse, and they are all painful. For the animals who experience them, and for us, who care and bear witness. And they are a direct contradiction of Article II that we UU’s have agreed upon.

Joanne Stepniak said, “The life spark in my eyes is in no way different than the life spark in the eyes of any other sentient being.”

I would like to paraphrase Thoreau and say, “Could a greater miracle take place than for us to look through another creature’s eyes?”

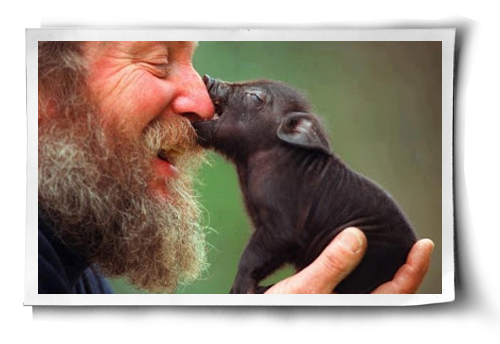

As a wildlife rehabilitator and caregiver to my own animals and others’, I sometimes say I’ve been drooled on, bled on, peed and pooped on, and bitten by almost every native mammal in the Northeast. And not for a moment have I been angry about that, only grateful that I could help.

I’d like to close with the story of the first animal I ever rehabilitated, a gentler tale. I was 23. So young. Still learning. Love and compassion spilled out of me.

I was living in Virginia horse country, riding the wrong side of a fence in the debate over hunting. My neighbors chased the foxes, and I healed their babies. And this is why.

Imagine, if you can, being a young vixen with a litter tucked deep into a den on a damp spring hillside. Your kits’ eyes are closed, their mewling sounding in your ears, their tiny paws kneading your body as they nurse. Hunger growls within your belly, but your mate has not returned for days from his hunting. Perhaps he has been the prey and not the predator. You get your kits settled, and take a chance. It is early morning, the fog just lifting from the hillside that is your home. Outside, the low-pitched sounds of field mice scurrying through the brush reach your sensitive ears. Your whiskers pick up movement in the tall grasses. Your belly propels you forward. You must eat in order to provide nourishment for your young. Now imagine that suddenly you hear the baying of hounds, and the thundering of hooves. Predators! You cannot let them find your kits, so you must run, lead them away. You run as fast as you can, away from the den, your heart pounding with adrenaline, your legs going numb with fatigue. Why do they chase you? Do they eat your kind? You can’t comprehend the reasons you are cornered against a large oak, hunting dogs advancing on you. Your last thought as their teeth tear into you is your kits. Will they survive? Why did this happen?

Those humans knew they did it for blood sport, for no other reason than tradition. They did this with no thought to the terror those animals feel, or the pain, or the young left behind.

Many of the orphaned litters were unknowingly left to die. Some, discovered by riders hours or days later, were brought to people like me to raise to young adulthood. Oftentimes by the same people who had contributed to the death of their parents.

My first fox rescue came in alone, no brothers or sisters to curl up against, no understanding of why he was there. He looked at me with wariness when I approached the cardboard box into which he’d been placed, and growled slightly until I scruffed him gently and deposited him into my lap, where he promptly peed.

But we sat there together, he and I, my lap damp but warm, my hand stroking his head. He relaxed his body, realizing I wasn’t going to hurt him. His head still had the dark grey, boxy look of a fox kit; his eyes were still a soft green, not yet turned to yellow. He was not the plumy red fox my neighbors wanted to hunt. Just a scared, rather pathetic little kit without his mother.

It was another two months before he was fully weaned from a baby bottle to a bowl, and he looked more ginger, and a month beyond that before his body lost its baby fat and his legs grew long and delicately thin, his black socks startling against the now red of his fur.

He spent more and more time digging into the hay and leaves of a horse stall that a friend had let me use, practicing his hunting on mice, eggs, or crayfish in a small kiddy pool, venturing toward his food or water bowls only after I had stepped away, developing the wariness of humans that might later save his life.

When the day came to relocate him to the woods that would become his home, I had to lure him into a carrier as he no longer fully trusted me. In the woods of Loudon County, I opened the carrier and expected him to dart out. I had set down and filled a large water bowl near the carrier, and scooped a big pile of dog kibble, to give him something to come back to if he needed it. A soft release, in a way.

To my surprise, he didn’t immediately run but stayed instead to sniff at the food, and then delicately lap at the bowl of water. I took a chance and let my hand slowly snake out, just for a moment gently dipping my fingers into the thickness of his fur. He tensed but stood his ground. I was lucky not to be bitten. I looked down at the bowl and saw his reflection and mine, merging together in a blur of identity, and then he darted away. Several minutes later, he stopped and turned his head. He gave me one long look through his catlike golden eyes, and then he was gone.

Thoreau argued in Walden that the divine exists not just in all people but can be perceived in all of nature. Finally, someone was acknowledging that God could be found in the eyes of a fox. There should not be dominion, but coexistence.

My fox didn’t contemplate the nature of divinity, and yet he was a sacred being. When he bounded away that day, there was a sense in my mind that I had completed a divine task. And the connection to the sacred was not being a “superior” being, but being a fellow creature.

One of the fundamental beliefs in many nature-based religions, and in the developing belief of UU’s, is that divinity is in all beings. One of the strongest laws of many pagan beliefs is to harm none. For in harming the earth or its creatures, we are showing the basest form of disrespect to the deities we honour. Thus in helping or healing the earth and its creatures, we are honouring those deities.

When I care for the dozens of animals that come through my clinic each spring and summer, animals that had become orphaned or injured as a direct result of human carelessness, I think of them as creatures who share the same spark of divinity that we all do.

We as UU’s have agreed that we honour all beings, not just humans. That we fight for their well-being. Albert Einstein said, “Our task must be to free ourselves by widening our circle of compassion to embrace all living creatures.”

Perhaps as individuals, we can start with one animal issue in which we can show kindness. Make a difference. Perhap you already have. Maybe at the end of the day, divinity might turn out to be more about empathy than anything else.

Benediction:

Albert Scheitzer wrote a prayer that I’ll share with you. “Hear our humble prayer, O God, for our friends the animals, especially for animals who are suffering, for any that are lost, or deserted or frightened or hungry; for all that must be put to death. We entreat them all thy mercy…and for those who deal with them we ask a heart of compassion and gentle hands and kindly words.”